And other stories from Bethlehem, Jericho, and Jerusalem

I’ve brought you materials to make your own islands, I told the kids, pointing to the giant bag of dirt I had lugged through the shuk of Bethlehem. They lit up. Let’s do it now, they said.

I marveled. They had flat-out refused to imagine islands in their minds, yet every child wanted a plastic container and some dirt to create a real island.

Twenty kids lined up patiently to take containers and to scoop handfuls of dirt. They weren’t picky about getting their hands dirty or pushing for their turn, both of which surprised me. How often do they play in dirt? How often must they wait for things they want?

The kids bolted in all directions. One tiny one climbed a big tree to find leaves and fruit, another two raided the mint garden. A whole bunch raced to the almond trees, picking raw almonds, eating some, putting some of the fuzzy green nuts into their containers. They picked unripe peaches (mishmish). One girl picked a red poppy and said it was the first time she had seen a flower with red, black, and white.

Ritab wandered off by herself down the hill. She was joyful and at ease in nature, leaning over prickly grasses to reach a single orchid pink flower. She proudly referred to her plastic box of dirt, raw almonds, and white flowers as her “white island”. She showed me the progress half a dozen times, beaming.

One of the littlest boys decided to step from the hill into the seating area, bypassing the stairs entirely. He dropped his island perfectly into the gap separating the two, and the dirt and raw almonds spilled out into cobwebs and dust. It was no matter. The two of us stuck our hands into the shadows, pulling out the weeds, rocks, and almonds that composed his island.

Each child had complete control over his or her island: nobody could tell them what should go where or damage the beauty inside. Each one treated their island as sacred property: some even carried the boxes on our hike to make sure they didn’t get lost.

There is ease of going with the flow, of letting the kids tell me what they need and following along, not clinging to my ideas about what they must learn. They didn’t want to imagine in their minds, they wanted to pick almonds from the trees and flowers from the meadow. They wanted to make the islands immediately. All okay, when I can let go of expectations and be with the kids as they are.

They don’t often get to experience nature like this in its bounty, don’t often play in fields instead of trash-filled streets. It doesn’t quite matter if they remember all the parts of the brain (although many do). What matters is they have these happy and peaceful memories to call upon when needed, that they have chances to touch beauty in nature when they’re young. Peace will come through joy, there is no need to force it in another way.

Mount of Temptation

A few weeks ago, Joann and I found ourselves in Jericho, one of the oldest inhabited cities in the world. We woke up in a refugee camp, scrambled to find anything for breakfast, and wound up in a taxi headed for the Mount of Temptation.

The Mount of Temptation is where Jesus was led into the wilderness to be tempted by the devil. He fasted for forty days and nights, and the devil came to him, saying: “If you are the Son of God, turn these stones into bread.” Jesus responded, “Man does not live by bread alone, but by the word of God.” Twice more, the devil presented Jesus with riches and temptation, and twice more, Jesus resisted: “It is written that we shall worship God, not riches of this world.” The devil left him.

Ever since walking into that holy church made of stone, I’ve been thinking about temptation. A temptation is something alluring, something that hijacks my emotional brain and leads me from rationality. What am I tempted by? What actions or thoughts of mine are pleasurable now but not healthy in the long-term?

Eating when I’m not hungry. I’ve noticed the craving to eat, especially unhealthy foods like falafel or an ice cream sandwich, arising when I’m feeling tired, sick, or uncomfortable. I look for food to comfort me and ease my physical or emotional pain — although sleep or a few moments of silence (free from technology) are often the best medicine.

Blaming myself and others when things don’t go according to my expectations. When things go “wrong”, I have a tendency to look for the root cause — who or what is to blame? This process of rationalizing my own lack of control is a form of self-delusion: it allows me to pretend that I can control my surroundings, if only this person or thing or action didn’t happen in this way. The wise path forward is to recognize the ever-changing and impermanent nature of the world. I will not always have control of the future. Instead of blaming, I can be intimate with my fear of the unknown, giving it space, letting it be without needing to use blame to wish it away.

Placing myself at the center of the world. I often see the behavior of others as being about me, instead of being their strategy to meet their own needs. If I’m not careful, this perception leads me to feelings of not belonging or not being valued, which creates separation in my mind where none was intended.

Believing that I’m not okay on my own. It’s tempting to believe that I’m not okay on my own: to look for intimacy and connection outside of myself as a means of healing my loneliness. I can offer space to my loneliness, this rejection of being alone, and transform it into a felt sense of sufficiency and wholeness.

Clinging to things to prove that I am loved and belong. I am constantly acquiring new things, be they handmade embroideries from Palestinian women, gifts of olive wood, or clothes and hats from dear friends. I don’t need all of these things to get by, but somehow having them in physical form is proof that I’m loved. When I carry my embroidered clutch, I remember the joy of discovering Silwan with Joann; when I see my pretty handbag, I recall dinner with the monastics in Doha with Lisa. Things are tokens that remind me of where I’ve been and who I’ve loved. But why do I need these reminders of love and belonging? I think it’s because of my fear that this love is no longer, that the passing of time and changing of circumstance will sever the intimate ties I have with others.

Saying goodbye to Joann on April 20th

Fear and abandonment arose for me when I dropped Joann off at the sherut that would take her to Tel Aviv. Fear that we wouldn’t speak again with the same intimacy, that I will be lonely, a genuine sense of loss.

And yet I felt the presence of Joann with me today. I sat in the spare bedroom at David’s house with all of the supplies Joann had gifted me in piles on the floor: stacks of colored paper, scissors, rubber bands, plastic containers for islands. Schedule in hand, I spent my morning preparing for the Dheisheh program that starts Tuesday, cutting name cards and books for the young ones. I felt Joann’s hands as mine crafting the paper books, her voice guiding me through the island meditation and brain explanation.

While I miss Joann, I know she will never leave me. She is in my teaching and the path that I am shaping in Bethlehem. My work is her continuation. There’s no turning away from that truth, even when I feel alone.

Saturday was a ritual of saying goodbye. Joann cooked Chinese stir-fry, boiled eggs for Seder, cleaned the fridge, did the dishes, and meditated, all before I woke up. I staggered out of bed as I normally do, in a daze. After a shower and breakfast of leftover soup, I was ready to face her. She was here, and tomorrow she would not be here. I tried to savor the moment. After breakfast, I shared with her the schedule of my children’s workshop at Dheisheh.

We headed out for a walk, winding through the streets of Abu Tor before arriving in Silwan, an Arab Palestinian village in East Jerusalem. An Israeli organization ELAD has created a new identity for this village: it is now the “City of David”, a Jewish historical site where tourists and settlers study the Jewish narrative.

Tunnels, dug ostensibly to gather Jewish historical artifacts, run underneath the homes of residents, risking their collapse. Israeli settlers claim homes here, declaring their presence in armored cars and Israeli flags. Settler guards train in the streets. The occupation is at work: the Israeli ELAD has schemed to take a historical site not given to them, and by my observation, the process is nearly done. Silwan and its Palestinian inhabitants are ignored, tourists flock to the City of David, homes are collapsing without building permits for repairs, and lands have been confiscated.

After Silwan, we took Arab bus 201 straight to Juliet’s house in the French Hill. On our walk to Juliet’s, Joann said that she had meditated on all of the people she had met here, and felt lucky to have had a witness to her journey. I agreed. In our processing and deep looking, Joann and I have revealed ourselves to each other: our narratives, our sensitivities, our preferences and joys. It has been a rich discovery.

We shared Seder with Juliet in her kitchen, ending with a delightful search for the middle piece of matzah. Joann had hidden it sometime during the meal, and Juliet and I searched the house for what felt like forever (but was probably only 30 minutes) before I found it under our table in the kitchen. Of course it would be right where we left it.

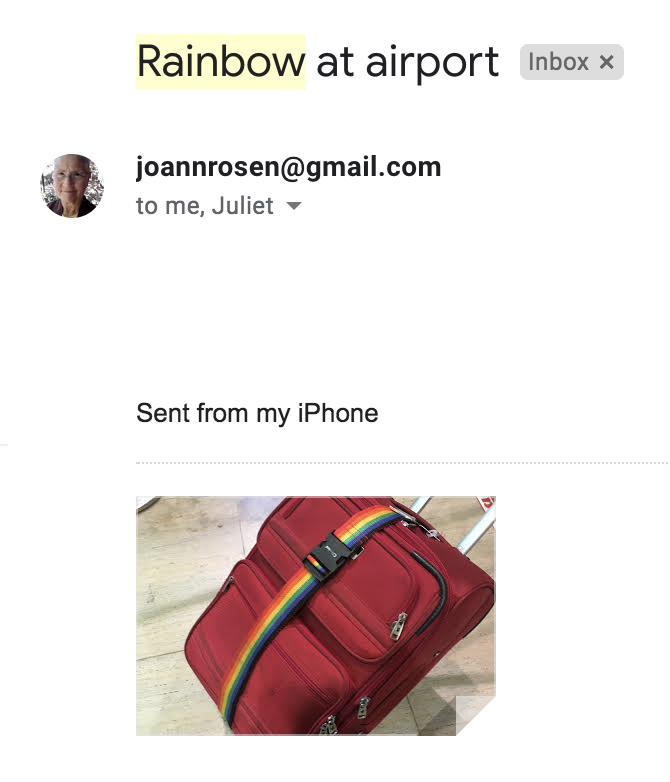

The tradition is that the youngest person gets to bargain for something in exchange for returning the matzah to the table. I asked Joann for a rainbow.

This morning, I awoke to this email from Joann.

She’s still with us, even in California.