Dear respected teachers and elders,

Dear friends on the path, near and far,

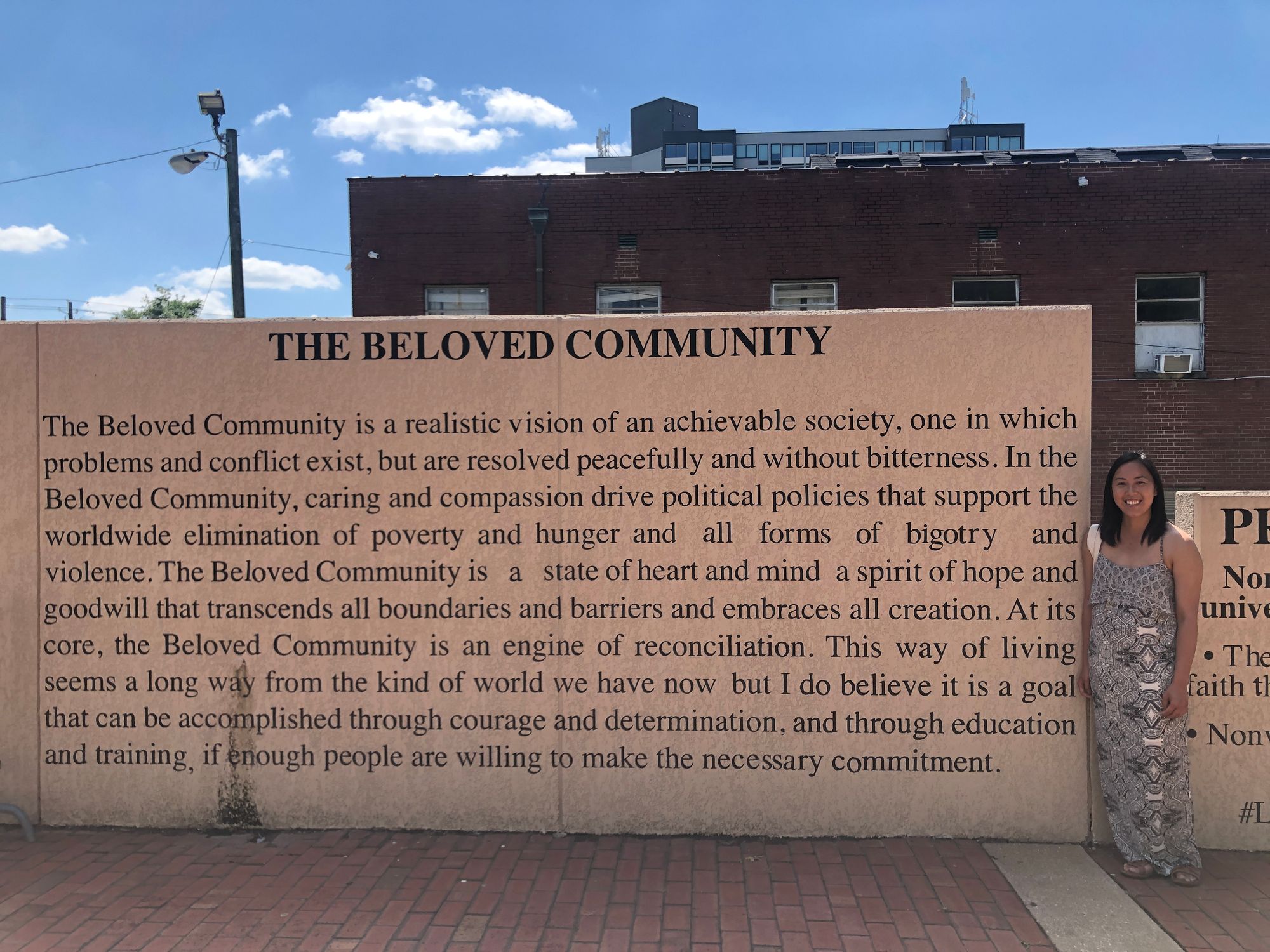

I was fortunate to be in Atlanta, Georgia, recently and to stumble upon Martin Luther King Jr.’s old church, Ebenezer Baptist Church, where both he and his father were pastors. Nearby, MLK’s nonviolence principles and his vision for the Beloved Community were painted on the walls. I want to share a few lines:

The Beloved Community is a realistic vision of an achievable society, one in which problems and conflict exist, but are resolved peacefully and without bitterness… The Beloved Community is a state of heart and mind, a spirit of hope and goodwill, that transcends all boundaries and barriers and embraces all creation. At its core, the Beloved Community is an engine of reconciliation.

MLK imagines a community in which there are no human enemies, a community that “transcends boundaries and barriers” and “embraces all creation”. My root teacher Thich Nhat Hanh talks about sangha in the same way: a community looking deeply in order to understand the suffering of others, so that this understanding may cultivate love. Thay does not discriminate; his vision of interbeing includes all of us. These two teachers and their shared vision for beloved community have been the foundation for my work.

I'd like to share about my work building the beloved community, starting with my time in Israel Palestine. I lived on and off in Jerusalem and Bethlehem – crossing political borders daily – for 20 months starting in August 2018, when I first arrived in Palestine to teach mindfulness in Aida refugee camp in Bethlehem. There I saw the possibility of simple practices – like inviting the bell, taking a moment to inhale before responding out of anger, the practice of conflict resolution – to heal and build harmony in communities of young people. To start creating conditions for these young people to step into their own liberation, to choose their response, regardless of their external conditions.

My heart was growing and softening as I shared spaces with groups of Palestinian women, cultivating joy through dance, music, and food in the midst of violence and war, and as I meditated with Israeli young people in shared spaces across Jerusalem. I learned about the fear and terror of the intifadas for Israelis, the worry that they were not safe in cafes, trains, in the course of their daily lives. I learned about the deep trauma of those of Jewish faith, the stories of persecution over generations. And I held the heartbreak of Palestinian families carrying the trauma of displacement as a result of the formation of Israel. My heart broke over and over and I could not take sides, only to hold the collective suffering and trauma with mindfulness and love.

A few months later I began co-organizing the first of multiple trips for Palestinian and Israeli young people to Plum Village, Thich Nhat Hanh’s monastery in France. What I learned in that trip and in the one to follow in 2019 was the power of bringing people together to see each other, to practice seeing no human enemy. These were young people who may have never met a person on the other “side”, the separation wall dividing folks just five kilometers away from each other.

We learned about each other in simple tasks, like booking travel to Paris. Those traveling with American and Israeli passports could book flights from Tel Aviv directly to Paris, without needing visas or going through other checks. For the Palestinians, the journey was much more difficult – requiring French visas, a border crossing to Jordan, and an average of about $800 more in travel fees. For the Israeli young people, this may have been the first time that they could see the barriers that their Palestinian counterparts faced in traveling.

Over this trip, the young people experienced simple moments of shared humanity – quietly drinking tea on Thay’s balcony at Plum Village, telling stories in tents late at night, eating croissants for the first time. This experience of coming together for a few days allowed us to see each other more fully, giving rise to the kind of community which could transcend boundaries and barriers – if even just for one gentle step, one shared meal. Thay’s sangha became an engine of reconciliation, shifting views that were stubbornly held, allowing space for abiding love.

I’ll end by sharing about Sit Walk Listen, a series of mindfulness gatherings held as public protests that I co-organized after the death of George Floyd under the knee of a Minneapolis police officer. I had returned from Israel Palestine at the beginning of the pandemic in late March 2020, to the news of George Floyd’s murder in May. In response, sangha friends and I gathered in public space outside of City Hall in San Francisco, inviting the public to join us in stationary meditation, slow walking, and listening circles. On that first day, 150 people came from all backgrounds, experiences, races and ethnicities, and were able to see each other in grief, anger, confusion, despair. People of color with relatives in the police force, Black parents worrying about the safety of their kids, Asians and Asian Americans reckoning with the fact that a Hmong American police officer stood by at George Floyd’s death, white folks looking to express solidarity and care, and many others. All of us human, mourning in our own way.

We made mistakes in these first gatherings, not realizing the number of people who would show up (up to 250) and not having deep experience in protest organizing. We learned that it can be vulnerable and scary to meditate in public with eyes closed, without any guarantee of safety. It can be scary to share vulnerable stories with strangers, unsure of how others will receive. Our main task as organizers was to facilitate spaces with enough safety so that people could find stillness and touch their own "Buddha nature" – their capacity for love, healing, and awakening.

To prioritize safety in listening circles, we utilized the Plum Village community's dharma sharing guidelines – confidentiality, sharing without interruptions or direct response, speaking in "I" statements and from personal experience.

To look after the public space, we asked those with certain types of privilege - often white or male-bodied individuals, those with American citizenship - to stand on the perimeters to welcome visitors, be they the news media, police, unhoused individuals, or curious passerby. This was a practice unto itself. These caretakers asked the news media to share their names and media credentials, to note where they’d be publishing our photos, and to ask anyone identified by face in photos for consent to share. For unhoused folks, caretakers would provide food, water, and masks, and an invitation to join if able. Sometimes we’d ask the police to practice with us. For those looking to disrupt, the energy of mindfulness settled even those with bullhorns or the loudest anger – some ended up in listening circles with us, sharing space with respect.

These spaces became opportunities for us as individuals to acknowledge collective suffering, to build empathy for those we might not see or understand, and to move towards holding each being as beloved. To see their humanity and our deep connection to each other. And to vow again and again to think, speak, and act in ways that support collective healing and liberation. In these events, I remember that the engine of reconciliation is ever moving through us - fueled by stillness and our own capacity to love.

Towards the end of our organizing in 2021, we began collecting donations for those in the community suffering from poverty and homelessness. One month, at Frank Ogawa / Oscar Grant Plaza in downtown Oakland, we filled two tables with personal hygiene supplies and non-perishable food items. Midway through our event, a person approached us asking for a few packaged cereal boxes. We gladly supplied them with as much food as they requested, and soon we had a steady stream of community members requesting food, water, soap, and other necessities for street survival. As organizers, we recognize that our sangha body is intimately tied to the wellbeing of the unhoused folks inhabiting our shared space. We must consider them as we gather, and commit anew to dismantling systems of oppression that contribute to their lack of shelter and sustenance. We must not let our practice be only for ourselves, or for those with the ability to inhabit our spaces.

I will end here, with the following questions: How do we keep our hearts open to others we don’t know and sometimes cannot see? How do we learn to see each other as human, to stop othering those that do not first appear like us? How do we continue to love in the face of such suffering? And how does that love manifest in action?